With a backwards spring, Mother Nature pitches a change-up after a fastball

With a warm March followed by a cold April, 2012 is shaping up to be the worst year for the Michigan fruit industry since 1945 or earlier.

Perennial crops in Michigan emerged from their protective dormant states much earlier than normal in 2012 due to an unprecedented heat wave during the middle of March. The abnormally warm March was preceded by an unusually mild winter across Michigan and the Great Lakes region, with mean temperatures during the December through February period generally ranging from 4 to 8 degrees F above normal. The winter of 2011-2012 was marked by five consecutive months of above normal temperatures back to October 2011. The coldest temperatures of the season in the fruit-producing regions of the state, generally in the -5.0 to +5.0 degrees F range, occurred during the third week in January and second week of February and caused little damage. The coldest temperatures were recorded in lower freeze prone areas.

Cold-sensitive fruits such as cherries, peaches and wine grapes are normally planted in high sites where the temperatures remained above zero. In addition to cold vulnerability, perennial tree fruit have a chilling requirement of 700 to 1,400 hours of temperatures between 35 and 45 degrees F, which normally prevents early growth in the spring. Even with the unusually mild winter temperatures, most crops had completed their chilling requirements in January and were just waiting for warm weather. Temperate fruit crops require temperatures above 45 degrees F for growth and the growth rate doubles for every 18 degrees F increase in temperatures. Normally, the number of warm days in March or April with temperatures above 45 degrees F is limited and frequent, colder periods slow or stop crop development. So, spring crop growth is typically slow and intermittent.

Summer-like March

The March 2012 heat wave began in earnest on March 11 and continued through March 23. The event was associated with a massive subtropical upper air ridge across central and eastern North America, which led to strong, southerly, low level winds across the region and the transport of tropical-origin air northward from the Gulf Coast region. Wind flow with the pattern was initiated and sustained by enhanced west-east differences in pressure between the low pressure over the western United States and abnormally high pressure over the northeast United States.

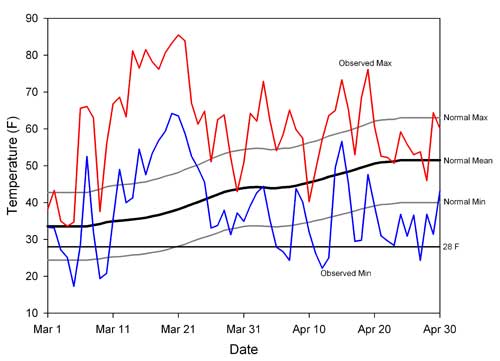

A representative plot of daily temperatures in Michigan during the event is given in Figure 1. At its peak during the third week of March, daily mean temperatures soared to 30 to 40 degrees F above normal and observed minimum temperatures exceeded the normal maximum temperatures by more than 10 degrees F. The heat wave resulted in many new climatological records, including the warmest March ever for Michigan as a whole with a mean temperature of 44.4 degrees F, which was 13.7 degrees F warmer than normal and 3.2 degrees F warmer than the previous record (1945). A new, all-time record for warmest temperature ever in March was also set, with 90 degrees F at Lapeer, Mich., on March 21.

Figure 1. Daily observed maximum (red) and minimum (blue) temperatures ( degrees F) at the Bainbridge Center, Mich., Enviro-weather automated weather station, March 1-April 30. Climatological normal maximum, mean and minimum temperatures (1981-2010) are provided in gray and black for comparison. The 28 degrees F line (black) is given for reference as it typically serves as an upper threshold for significant cold damage in tree fruit at and following bloom.

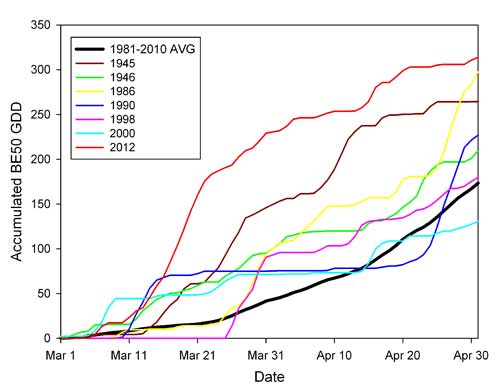

For some historical perspective, base 50 degrees F growing degree day accumulations (a strong proxy for the rate of plant growth and development) are given for 2012 and the six warmest Marches on record in Figure 2. In 2012, degree day accumulations surged during the second and third weeks of March in response to the heat wave, quickly surpassing the levels of all other warm Marches including the (previous) 1945 record.

Figure 2. Accumulated base 50 degrees F growing degree totals at Benton Harbor, Mich., for the March-April period for 2012, the 1981-2010 normal and the warmest six Marches on record (prior to 2012). Growing degree day totals were calculated with the Baskerville-Emin methodology.

In terms of impacts, the heat wave led to rapid early growth and development across Michigan. Rapid plant growth continued as highs rose through the 80s and warm, nighttime temperatures allowed plants to grow both day and night. By late March, tree fruit development was at least four weeks ahead of normal. For example, in southwest Michigan a rapid bloom sequence occurred from March 18-23 with a different fruit species opening every day. Apricot bloom began on St. Patrick’s Day (March 17) and the trees were in full bloom by March 18 – the average full bloom date for apricot in southwest Michigan is April 18.Japanese plums reached full bloom on March 19 – the average is April 21. Peach bloom began and reached full bloom for many varieties on March 20, the first day of spring – the average date is April 27. In sweet cherries, full bloom was March 21-22, depending on the variety – the average date is April 25. Tart cherries, European plums and pears all began to bloom on March 22. These fruits normally reach full bloom in mid-April.

By March 23, apples were in the pink stage, just before bloom and in southwest Michigan, Zestar (an early variety) was at first bloom. The average full bloom date for apples in southwest Michigan is May 6-9, depending on the variety. In 2012, apples bloomed about five weeks earlier than normal. Grape growth in southwest Michigan had begun with budburst on about March 21, which normally occurs about April 25. The earliest date for bud burst in southwest Michigan in the last 30 years was April 14, a full three weeks later than 2012. Blueberries were at pink bud with some open bloom in early varieties such as Bluecrop – normally, blueberry bloom is in mid-May.

When fruit trees are dormant they can withstand very cold winter temperatures, but as they develop in the spring, warmer and warmer temperatures will cause injury. By bloom, temperatures just below freezing can kill the flowers and reduce the size of the crop. Temperatures below 28 degrees F cause significant injury and temperatures below 24 degrees F are cold enough to kill almost all the fruit. Overall, the abnormal warmth of March pushed crops far ahead of normal growth stages so early in the growing season, leaving them highly vulnerable to injury from spring freezes.

The return of a normal spring pattern

Unfortunately, no location in Michigan has ever experienced an abnormally warm March that has not been followed by freezing temperatures during April, May or June. On March 24-25, the upper air jet stream pattern that produced the heat wave broke down and was replaced by a troughing pattern across the Great Lakes region that led to the passage of a cold, dry, Canadian air mass through Michigan and freezing temperatures over much of the state on the mornings of March 26-27. These initial events caused widespread severe damage to cherries that were in the swollen bud stage across production areas of northern Michigan and to many tree fruit in eastern Michigan where peaches were in full bloom.

Between the late March upper air pattern change and the present, more than 15 freeze events, including at least five with minimums below 28 degrees F, occurred across Michigan. This is climatologically greater than normal, as the average number of daily spring freeze events (32 degrees F or less) after March in a given season ranges from about eight in the southwest and southeast corners of the state, to more than 20 in interior northern sections of the state. Normally, perennial plant growth begins in southern Michigan and slowly progresses northwards with the advance of warmer temperatures in the spring. It is not unusual for the apple production region around Grand Rapids, Mich., to be one or two weeks behind the fruit production centers of southwestern Michigan and the cherry production areas around Traverse City, Mich., to be another one or two weeks behind Grand Rapids, Mich. The rapid growth during the March 2012 heat wave resulted in a much smaller difference in growth stages across Michigan. Instead of a month’s spread in development in April, there was only about a week of difference between the northern and southern growing areas.

Normally, freezes that cause widespread damage in southwest Michigan cause little damage to the north where plants are not as advanced. Conversely, damaging freezes in the northern or central fruit growing regions may cause little damage to the south because damaging cold does not extend southward.

Damage from the freezes in April 2012 was widespread and damage varied depending on the type of freeze and the stage of development of the fruit. Figure 1 shows the freeze events in southwest Michigan. Every time the temperature dropped below 28 degrees F there was significant injury to tree fruits and grapes. Some of the freezes were of the advective variety in which subfreezing temperatures were accompanied by surface winds (e.g., March 26), accentuating the magnitude of cold injury and causing fan-based frost protection equipment to be much less effective than is normally the case (by reducing or removing any surface temperature inversion). Many tree fruit and southern grape growers suffered significant losses to the early freezes in April and each additional freeze removed an additional portion of the entire remaining crop. The hard freezes at the end of April again caused widespread damage across the state and killed most of the remaining fruit in all but the best orchard sites or in isolated locations that somehow escaped severe cold.

One concern expressed by many growers is whether this spring’s highly abnormal weather is the result of simple weather variability or part of a longer term trend. Given that the heat wave responsible for the abnormally early start of the season and subsequent freeze events were directly associated with jet stream patterns (i.e., temperatures at the time of our heat wave were much colder than normal over much of Europe, Asia and Alaska), the initial response is that it was simply a part of short-term “weather” variability. However, there is some evidence to suggest the root cause is not so straightforward. For example, the early warm up this season does fit with a trend towards earlier onset of spring (the seasonal warm up in Michigan is occurring about seven to 10 days earlier now that it did in the early 1980s).

In addition, the factors involved with the flow and evolution of the jet streams around both hemispheres are physically linked, even in potentially perturbed climates of the future. Another key issue is the expected frequency of occurrence of such extreme events in the near future. Given how unusual this past March was and assuming relatively slow trends in climate over time, one would not expect to see anything like it in many decades or longer. At the same time, we do have an example of “lightning striking twice” in the historical records: The previous record-warm March of 1945 in Michigan was followed by another much warmer than normal March in 1946 (see Figure 2). The moral? Expect a much less stressful early growing season in 2013, but don’t completely count out the possibility of yet another weather-related “change up.”

Additional Information

- MSU Extension's 2012 Fruit Freeze Resources

Print

Print Email

Email