Nitrogen fertilization of the 2016 wheat crop

Growers are making plans for topdressing wheat with nitrogen. Predicting optimum nitrogen rate is difficult, but there are considerations that may help growers arrive at a reasonable estimate.

Wheat responds to nitrogen (N) more than any other nutrient. However, the optimum rate and application timing of N in any given season can be highly variable. This is due, once again, to the unpredictable nature of weather. Not only does weather, particularly rainfall amounts, affect the extent to which the crop can utilize N, but it also effects the amount of N the soil is able to retain for the crop’s use. The other reality that weighs-in this season is commodity prices have weakened considerably and, consequently, the cost effectiveness and use rate of all inputs need to be re-evaluated.

Michigan State University Extension’s “Nutrient Recommendations for Field Crops in Michigan” (E2904) recommends the following formula for N rates for wheat: N pounds per acre = (1.33 x yield potential) - 13. In this formula, the total N recommendation includes any N applied in fall at seeding. For example, in a field having a yield potential of 80 bushels per acre, one would apply 93 pounds per acre of N [(1.33 x 80 bushels)-13]. If 20 pounds was applied at seeding, the remaining 73 pounds would be applied in spring.

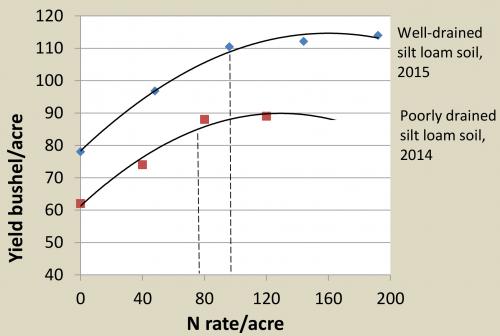

For growers using 10 pounds per acre of N or less in fall, this recommendation roughly translates to springtime use rates of 1.0 to 1.1 pounds per acre of actual N for every bushel of potential yield. For fields that deliver relatively low grain yields, the 1.0 pounds per acre may be sufficient, whereas fields with high historical yields may benefit from the 1.1 ratio. The figure provided is to simply illustrate an example of the difference in yield response to N. A 1.0 ratio of N pounds per acre: bushels per acre best approximated the optimum N rate for the poorly drained site in 2014, and a 1.1 ratio for the 2015 site with its inherently higher yield potential.

Wheat yields in response to nitrogen rates in Michigan’s Thumb region.

Before settling on a specific N rate, growers might fine-tune their actual rate based on other considerations:

- Fertilizer N rates can be reduced where other sources contribute to the N supply. Examples might include where manure was applied or where soil contains a high level of organic matter.

- Reduction in wheat prices should place a constraint on N rates. With intensive wheat management, yields tend to increase with additions of fertilizer N. However, the return on investment is curtailed as N rates increase. As an example – and to over-simplify – if wheat is worth $4.20 per bushel and the cost of N per pound is $0.42, then a grower would need to achieve at least 1 bushel of grain for every additional 10 pounds of N.

- A wheat crop that is not protected from leaf diseases is more apt to have a lower wheat yield and, therefore, a lower requirement for N.

- To minimize the risk of lodging, growers would do well to particularly avoid excessive N rates in those fields that achieved an abundance of growth last fall. Fields that are most prone to lodging are those that were planted relatively early or a high seeding rate was used.

- Growers should avoid spreading on frozen ground as it is environmentally unsound and can lead to significant N loss. An option following soil thaw is to apply N when morning temperatures dip down to temporarily freeze the soil surface to the extent that it can support equipment traffic. This scenario usually allows the nutrient to settle within the soil once the temperatures warm later in the day. An early application is most appropriate where wheat stands are thin or showing poor vigor following the winter months.

- Where early spring stands are relatively strong and dense, delaying N fertilization until a couple of weeks following green-up or even until full-tillering may lead to greater use efficiency. This timing may avoid the saturated soil conditions and N loss that often occur with earlier applications. In central Michigan, this timing often falls between mid- and late April. This practice can especially work for those that choose to apply all N in a single application.

In time, additional field research should help to better predict optimum N rates for individual Michigan wheat fields. Until then, growers might consider conducting some field trials in their own fields comparing various rates of N.

Print

Print Email

Email