Managing mummy berry shoot strike infections

Information on preventing mummy berry shoot strike infections in Michigan blueberries this spring.

With spring, a blueberry grower’s thoughts turn to preventing mummy berry. Warm weather has blueberries growing rapidly and leaf tissue is quickly emerging. This young tissue is susceptible to infection by mummy berry (Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi).

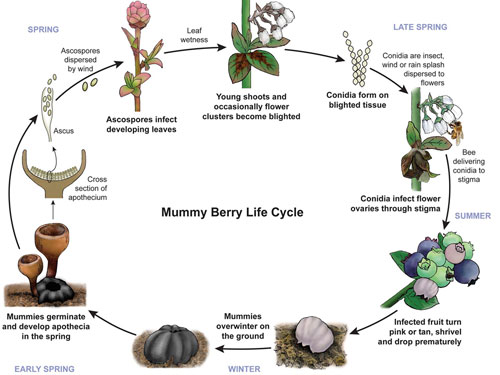

Mummy berry needs to infect blueberries twice every year to survive. Spores from overwintering mummies need to infect the new growing shoots. This primary phase of the disease is commonly known as shoot strike. Early disease control is focused on preventing shoot infections. Infected shoots die and spore from these infections are spread to the flowers during bloom.

The primary phase of mummy berry (shoot strike) is on the left side of this diagram of the mummy berry life cycle. Source: Michigan Blueberry Facts: Mummy Berry (E2846)

Mummy berry apothecia, called trumpets or mushrooms, have emerged from the mummies in southwest Michigan. Mushroom numbers so far are low to moderate, perhaps due to drier conditions since mid-April. Rains may result in a second or third flush of apothecia. If apothecia are present as well as green leaf tissue, blueberry growers need to protect against mummy berry.

As the leaf buds expand, the exposed leaves are susceptible to infection by ascospores from the apothecia. Ascospores are often discharged in the morning when relative humidity drops and the wind speed picks up. Ascospores are dispersed by the wind and can move a good distance from the apothecia. Spores can blow in from neighboring fields or from volunteer or wild blueberry bushes around the field. Growers should monitor their fields for mummy berry trumpets and watch the weather to anticipate disease infection periods.

The ascospores need water to germinate. For an infection to occur, the leaf tissue must be wet long enough for the fungal spore to germinate and infect the young tissue. Paul Hildebrand of Ag Canada in Nova Scotia has determined the infection conditions necessary for shoot infection in lowbush blueberry; these seem to hold up for highbush blueberry as well. At 57 degrees Fahrenheit (14 degrees Celsius) with adequate moisture, infection occurs in five to six hours. At 36 F (2 C), 10 hours of leaf wetness are required for infection. The warmer the temperature, the shorter the wetting period required for infection. The optimum temperature for infection is about 68 F. Over 80 F, conditions are less favorable for fungal growth and the fungus needs longer wetting periods for successful infection.

Table 1. Mummy berry shoot infection conditions.

|

Wetness |

Average temperature (F) during wet period |

||||

|

Duration (h) |

36 |

43 |

50 |

57 |

65 |

|

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

6 |

0 |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

|

8 |

0 |

Mod |

High |

High |

High |

|

10 |

Mod |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|

15 |

Mod |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|

24 |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

Source: Paul Hildebrand, Ag Canada, Nova Scotia

Growers can use Table 1 to estimate risk in their blueberry fields. You can also use Michigan State University’s Enviro-weather website to monitor for mummyberry infection conditions. There is no specific mummy berry model, but blueberry growers can use the Multi-Crop Disease Summary tool in the fruit section of Enviro-weather. This tool reports the hours of wetness and the average temperature during a wetting period for all the stations in the region. The columns for duration and average temperature are located near the middle of the table. This tool can be used to estimate the risk on your farm by comparing similar or nearby stations. This allows growers to determine the disease risk during or soon after wetting events. In 2014, we plan to have a mummy berry model available for Enviro-weather.

Another important disease control decision is what fungicides to use in your mummy berry control program. Some of the more effective mummy berry fungicides are shown in Table 2. Some materials work well against both phases of the disease, but most are better against one or the other. Fungicides that are effective at preventing shoot strike are materials that are good at protecting young leaf tissue, usually under cooler spring temperatures. The table groups materials by whether they are systemic or protectant fungicides.

Table 2. Fungicide efficacy against mummy berry in blueberries

|

Fungicide |

Specific infection controlled |

|||

|

Trade Name |

FRAC Code |

Shoot strike |

Fruit rot |

|

|

Systemic fungicides |

||||

|

Indar |

3 |

+++ |

+++ |

|

|

Quash |

3 |

+++ |

+++ |

|

|

Orbit |

3 |

+++ |

++ |

|

|

Omega |

3 |

++ |

++/+++ |

|

|

Pristine |

11/7 |

++ |

+++ |

|

|

Quit Xcel |

11/3 |

++ |

++ |

|

|

Protectant fungicides |

||||

|

Serenade + Nu-Film |

44 |

++/+++ |

++ |

|

|

Sulforix |

M2 |

+++ |

++ |

|

|

Bravo |

M5 |

++ |

+ |

|

|

Ziram |

M3 |

++ |

++ |

|

Protectant fungicides are deposited on the surface of the plant and kill fungal spores as they germinate. Protectant materials need to be applied before the infection event to be effective. Systemic materials are absorbed into the plant and kill the fungus as it tries to penetrate the plant. The table also shows the FRAC (Fungicide Resistance Action Committee) code. The FRAC code indicates the mode of action of the fungicide. To reduce the risk of fungicide resistance in the mummy berry fungus, it is a good idea to use fungicides with more than one mode of action to control mummy berry. This can be done by alternating materials with a different mode of action (FRAC code) between sprays or mixing materials with different modes of action.

The new fungicide Quash is as effective as the current grower standard Indar. Quash has a seven-day PHI (Indar and Orbit have a 30-day PHI) and has excellent activity against phomopsis and moderately good activity against anthracnose fruit rot. Quash, Indar and Orbit all belong to FRAC group 3, meaning they are sterol inhibiting (SI) fungicides and have the same mode of action. There are minor differences between the compounds in the same group, so some are more effective than others against the same disease.

The SI fungicides are readily absorbed into the leaves and kill the fungus as it penetrates the leaves. This group of fungicides moves throughout the leaves where they were applied and provides protection until the growth of the leaf dilutes the fungicide concentration, making it no longer effective. This period of protection is about four to five days or less, depending on the rate of growth of the plant. The SI fungicides can kill the fungus soon after the initial infection while the fungus is still small. This ability to kill the fungus after the initial infection gives these materials back action of about 24 hours. This gives growers the ability to wait for an infection period before applying a fungicide control.

FRAC group 11 comprises the strobilurin fungicides (e.g., Abound, Pristine). These materials are absorbed as well, but are generally weaker at killing fungi after an infection, i.e., they have less post-infection activity, and Michigan State University Extension recommends they only be used as protectant fungicides and should be applied before, not after, infection periods.

FRAC group 11 fungicides tend to have a strong affinity for the waxy layer on the plant surface and are less susceptible to wash-off from rain. However, they have a high risk of fungicide resistance development and a lower efficacy against mummy berry shoot strike. These products are recommended for application at or after bloom, when they also control other diseases such as phomopsis and anthracnose.

Finally, there are the true protectants such as Ziram and Bravo. FRAC codes beginning with M denote that the group has multiple modes of action and are less susceptible to fungicide-resistance problems. Protectant materials remain on the plant surface and are often tank-mixed with systemic materials. The advantage of mixing two materials with different modes of action is that it reduces the risk of fungal resistance to a specific group of fungicides and mode of action and giving a longer period of control with a protectant material on the outside of the plant.

An effective mummy berry control strategy requires that growers understand the disease and the strengths and weakness of the control products available to them.

Also see:

- Scouting and management of mummy berry in blueberries

- Understanding mummy berry shoot strikes

- Mummy berry poised for action in blueberries

- Warm weather and a wet weekend put blueberries at risk for mummy berry

- Preparing and using mummy berry observation stations in blueberries

Dr. Schilder's work is funded in part by MSU's AgBioResearch.

Print

Print Email

Email