Dangerous currents on the Great Lakes – know how to save your life

Enjoy the Great Lakes, but also learn how to save yourself if you are ever caught in a rip or channel current.

Recent news stories on drowning deaths in Lake Michigan are unfortunately all too common. According to the nonprofit Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium drowning is the number one cause of accidental injury death in children ages 1 to 4. More than 10 people drown in the U.S. every day. Enjoying swimming and boating in the lakes is one of the great benefits Michigan offers, but it's important to understand the power of the lakes and practice safety precautions.

Water safety tips

The Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium whose mission is to help people safely enjoy the Great Lakes and to end drowning, offers Top 10 Lifesaving Water Safety Tips/Best Practices which includes resources for parents and educators, too. Additional Great Lakes beach safety information and resources can be found at the National Weather Service website.

Swim risk category

The National Weather Service also provides surf forecasts which include swim risks ratings describing conditions at Great Lakes beaches and national coastal beaches. It's a good idea to check out the forecast before you head to the beach, but remember that even a low risk rating means you still must practice safety measures while swimming.

- Low Risk - Large waves and dangerous currents are not expected, however dangerous currents may exist at any time near piers, breakwalls, and river outlets.

- Moderate Risk - Breaking waves and currents are expected. Stay away from dangerous areas like piers, breakwalls, and river outlets. Always have a flotation device with you in the water.

- High Risk - Life-threatening waves and currents are expected. Stay out of the water and stay away from dangerous areas like piers and breakwalls.

Understanding currents

Channel currents and rip currents are dangerous currents that are found in the Great Lakes. Rip and channel currents are often incorrectly referred to as undertows, but rip and channel currents do not pull a person under the water. Rip currents can pull a swimmer away from the shore; channel currents move people parallel to the shore. Depending on the weather conditions and land formations, rip currents typically flow perpendicular (at a right angle) from the shore toward the lake. Channel currents generally flow parallel to the shore. The currents become dangerous when swimmers try to fight against them, become tired and then often panic.

How rip and channel currents form and how to escape them

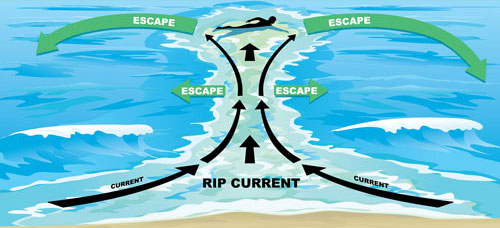

Rip currents form when waves break over a sandbar near the shoreline, piling up water between the breaking waves and the beach. One of the ways this water returns to the open water is to form a rip current, a narrow but powerful stream of water moving swiftly away from shore as it breaks through the sandbar. To escape a rip current, you should go with the flow of the water until the current dissipates and swim parallel to the shoreline. Once out of the current, swim back toward shore.

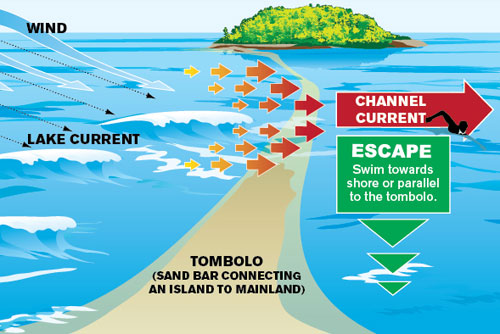

A channel current flows parallel to shore, between the beach and an island. A channel current forms when the presence of a partially submerged sandbar connector between the mainland and an offshore island causes the flow of water to speed up as it goes between the island and the shore. A channel current looks like a river running parallel to shore. A swimmer can be pushed off the sandbar or swept to either side of the sandbar. Swimmers tend to panic and try to get back to the “safety” of the unstable sandbar, rather than swimming to the shore. This may eventually exhaust swimmers, resulting in drowning. To get out of a channel current, swim toward shore rather than swimming back to the unstable sandbar. Even if the sandbar may be closer, swim toward the shore ─ this is the best route to safety.

Steer clear of the pier

Another important current to understand is a structural current. Currents found alongside or as a result of structures like piers and breakwalls — called structural currents — are usually always present. Structural currents are dangerous on their own, but when paired with other currents or when colliding with incoming waves, the combination can move a swimmer from one dangerous current area to another with no clear path to safety. Swimmers should avoid jumping off or swimming near piers. It may seem safe to stay close to a pier but the currents found along these structures are often dangerously strong.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This article was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA180AR4170102 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statement, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email