A tip for dealing with the “Help, my spruce are dying” requests

Editor’s note: This article is from the archives of the MSU Crop Advisory Team Alerts. Check the label of any pesticide referenced to ensure your use is included.

Good spring weather always brings a flood of spruce samples and phone calls about dying spruce trees to the lab. The clients often have several spruce trees in varying stages of decline and are panic stricken, desperately searching for any easy fix to stop the “disease from killing other trees.” Two people I spoke with last week had done Internet searches and were fairly confident that their trees were being killed by Rhizosphaera, a fungal needlecast pathogen. Not to discredit the destructive potential of Rhizosphaera, I am after all a plant pathologist, but initially I try to get a larger picture of the health of the tree in question.

With spruce samples in particular, it is helpful to look at the amount of growth that the tree produced during the last few growing seasons. That alone can tell a lot about the history and overall health of the tree. Based on experience garnered from looking at hundreds of spruce samples, we expect to see a minimum of six inches of growth per year on a healthy, well-established spruce. This is a benchmark to which we compare most spruce samples. In order to do this, let’s first review the mechanics of conifer growth.

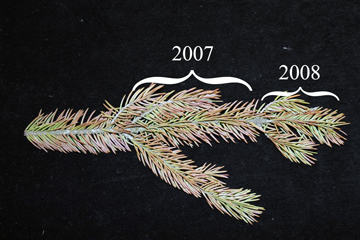

Toward the end of every growing season buds are produced at the end of each branch, these buds will produce the following year’s shoots. The bud is surrounded by scales that protect it throughout the winter. In the spring, the bud elongates producing new shoot growth. The scales that once encased the bud fall off the stem, leaving behind scars (see Photo A). The presence of these scars is used to measure annual shoot growth. In the spring, before new growth begins, measure from the tip of the branch back to the first set of bud scale scars, this is the amount of growth produced in the last growing season. Next measure from the bud scale scars closest to the tip back to the next set of scars, this is the growth that occurred the prior year.

Using this bud-scale-scar-technique the growth produced in 2007 and 2008 has been indicated on the images shown. Photo B shows a healthy, well-established spruce currently growing in the MSU Horticulture Gardens. In both years, the tree produced approximately nine inches of growth per year. Photo C shows a spruce sample that was submitted to the lab. In 2008 the tree produced approximately one inch of growth while in 2007 it produced approximately two and a half inches of growth. As it turns out this tree was transplanted in early 2007. The client watered the tree minimally in 2007 and did not water it in 2008. This tree was in a serious state of decline, the browning and needledrop present throughout the tree was a result of transplant stress, not Rhizosphaera. I recommended that the client forgo the fungicide treatments he wanted to apply for disease control and provide the tree with good, cultural care to mitigate the transplant stress and promote good root growth. Even without knowing the history of this tree, measuring the annual growth was a major factor in our diagnosis. This technique is quick, easy, and can be done in the field by anyone involved in caring for or assessing tree health.

Print

Print Email

Email